EICEV, the second international meeting of Venezuelan specialty coffee, is an important event. It crystallizes the influence of this growing movement focused on coffee quality within the country. Just a few decades ago, the country produced coffee and exported some of it internationally. Nowadays, cocoa is the only product to make a name for Venezuela's terroirs. And then there's rum. Everyone knows about diplomático, el problemático.

chapter 13

Returning to Venezuela means elucidating this paradigm, retracing history and understanding the whys and wherefores of events. Venezuela borders Colombia and Brazil, both of which have a proven reputation for quality coffee. The Cosiata of 1826 marked the separation of Venezuelan territory from the union of countries to the north of South America. Since 1819, Venezuela had been a single country with the territory we now know as Colombia. It's a fact we like to remind ourselves of to justify our quest for quality in Venezuelan coffee. With Colombia so much at the forefront of specialty coffee trends, it's a wonder that Venezuela has lagged behind and is only now making its way into specialty coffee. Since 1830, Venezuela has been considered a nation in its own right. Economic and political conditions are very different from one country to another, even though they are neighbors. For Venezuela's coffee sector to flourish, all that remains is to learn the best lessons from neighboring countries to make up for lost time.

At the time of writing, it's no secret that the coffee qualified for the EICEV auction is an exceptional one. Each grower has done an admirable job to produce a coffee of this quality. I'm extremely lucky to have been able to taste all the coffees that took part in the meticulous sensory evaluations by several Q graders. But when the applications to join the jury opened, I had no idea that I would end up among those selected.

Juan and I were in Carora, spending time with our family. It was just after we'd visited Juan Carlos' farm, and we were planning to head west, closer to Boconó and up to the state of Mérida. In Tovar, there's Edwin and Adnoldo's farm. Then, one day, we saw an offer to become a coffee taster for the EICEV. We didn't know much about it at the time, but we sent in our applications anyway.

It's funny to change routes like that. We were back in Caracas, not knowing for how long. What we did know was that we wanted to see how the event was organized, how the coffee was selected and who were the lucky, qualified people on Venezuela's panel of coffee tasters. If we didn't come away chosen to evaluate the coffee, at least we'd have met some nice people and learned a lot.

We had arrived at the Ministry of Agriculture to undergo a calibration phase among 30 professionals in the coffee world. The person who was going to calibrate us, to guide us in the evaluation of the coffee so that we could be as homogeneous as possible in our ratings, was Claudia Pedroza. Taster and roaster, Q grader and head of quality control at Cafeologia, and as if that weren't enough, judge of the cup of excellence in Mexico. We gave a quick introduction to each person present. Darveris Rivas, Juan Manuel Silva, coffee growers were on the organizing side of the whole event and were taking part in the calibration phase that would determine the members of the coffee selection jury for the national phase. We were well surrounded.

Among the candidates who came to try their luck were the best baristas, roasters and professionals in the industry. Some of them I already knew, and I was happy to see some familiar faces. Francesco Guerrieri, David Bracamonte and Ramon Tarbi all work in coffee shops, the places to be for specialty coffee. Ramon works at Cospe café, Joel Perez's coffee shop. For David, it was a chance meeting. A stroll to kill time at the San Ignacio shopping mall. In the distance, I spotted a kettle with a gooseneck. It was a sure sign that I needed to get closer. David was on duty and, in response to my curiosity about the origins of the coffees he served, we quickly talked about preparation methods, processes and our plans to visit the country's farms... He works at Café Melosa, a coffee shop-roastery in Caracas that offers coffee from several regions of the country. He tells me that the brand's founder was impressed by the whole coffee movement in Colombia, the organoleptic quality and the visibility that some of the best Colombian producers have thanks to the niche sector that specialty coffee still represents. At Café Melosa, we love good coffee and David proves it by representing his work as a barista to the best of his ability and being the best ambassador for the work of the producers of the coffee he offers me. I spent a good part of the morning at the counter, happy just to be able to be there and drink good coffee. Little did I know that our paths would cross again. And so it was during the calibration phase.

In the end, they all knew each other. I noticed that the average age was very young. Really young. But I thought it was beautiful. What stood out was their commitment. They've given their all to the café, and they're all experts in their field. We were all committed to Venezuelan coffee. The responsibility was great. Our mission was to put our sensory skills to work for the producers. To give the coffees a chance. While remaining objective. To accept that some coffees might not achieve the required attributes. But never forget that behind each coffee, several hands, several months of work had been devoted to the coffee. Behind the scenes, four roasting machines, professional grinders, huge kettles and the accompanying gas stoves. We were in the temple of coffee! And we were going to devote the next two days to Venezuelan coffee. Learn how to evaluate coffee, how to grade coffee, how to prepare the tasting table. Serving coffee into cups. Smell coffee, taste coffee. The moments of deliberation after tables of ten coffees were the most instructive. Extrapolating coffee notes to other people is a very rich experience. For Juan and me, it was like a sensory analysis course, only better.

A day at the beach. We needed it. We cross the mountain range that separates the capital from the coast and here we are. Feet in the water. It's good. And so is the guarapita. The announcement arrives just then. I receive a message. I've been asked to taste the coffees of 180 of the country's producers. Gratitude and a sense of peace. Events align with the path we've come to take and show us the next steps to follow. This spirituality comes to me as I write these words and recall the events. But in reality, the task was not an easy one. A busy week dedicated to coffee, with the responsibility of selecting the best producers through their coffees.

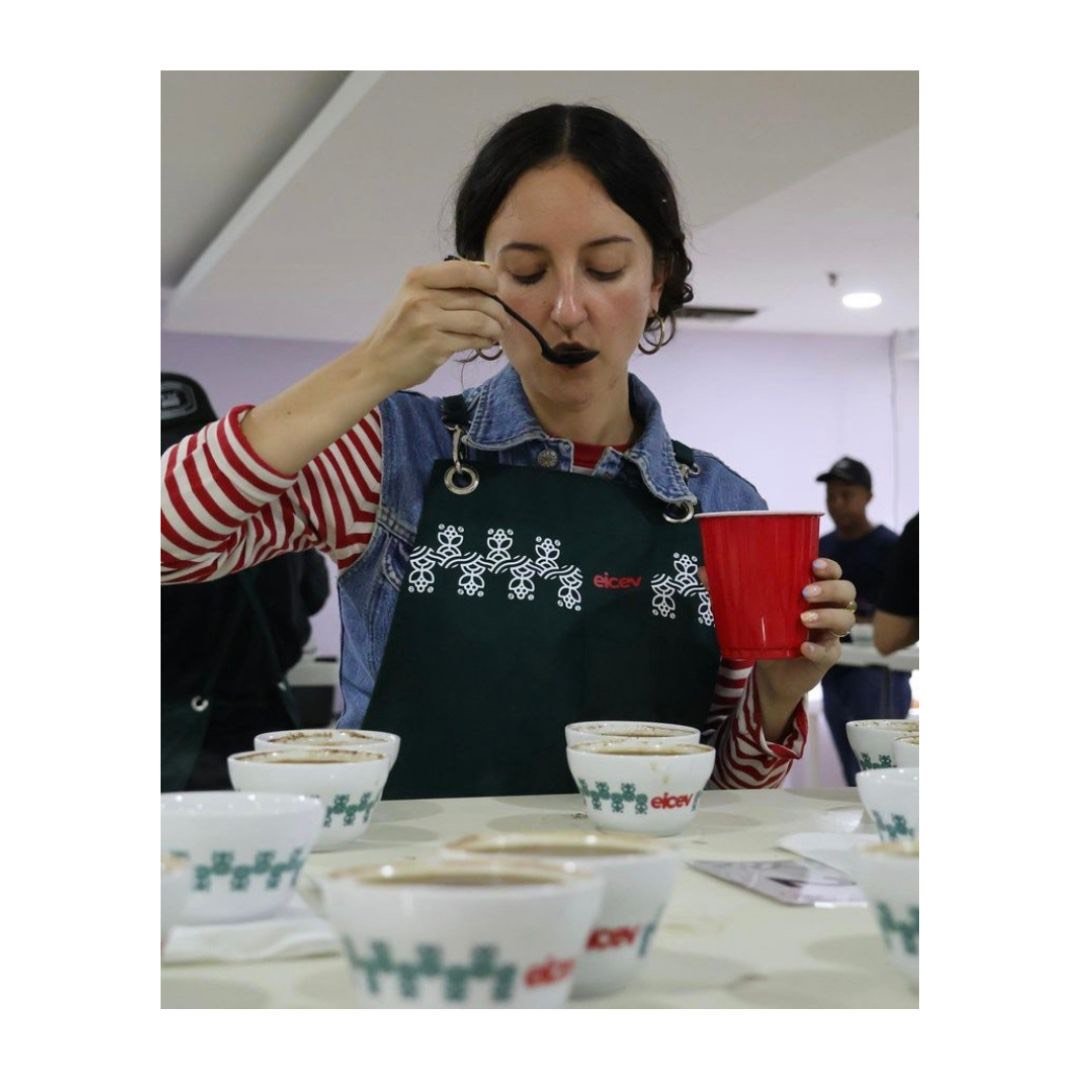

So I was back to the temple of coffee with the other tasters. I really liked the rhythm. Having breakfast with Juan. Getting ready to leave in the cab and marvelling at the chance to be in a city I love and to enjoy the spectacle it offers. The days were filled with... coffee! The pace was demanding. Four to five tasting tables of ten coffees a day. A whole week. The coffees are classified by process. We taste washed coffees with washed coffees, natural coffees with natural coffees, honey coffees and fermented coffees separately. This makes for a more objective assessment. The coffee is roasted the day before and ground just before it is served on the tables. We smell and rate the coffee by its fragrance, dry. We lift the lids of the cups, insert our noses and close them again, so that the odor molecules remain inside. This operation is repeated for each cup, with a second or even third round. Then come the event volunteers, who do their utmost to ensure that the sensory experience goes as smoothly as possible. They bring the kettles. The water is poured in a very precise and meticulous way to create the right whirlpool so that the coffee moistens evenly and stays on the surface of the water. We wait four minutes. It's time to break the crust. You bring your nose close enough to smell the first aroma of the brewed coffee. This step should be carried out as quickly as possible, to try and break all the crusts at short intervals. Then we taste. The room fills with silence and slurping. Slurping is the verb I think best describes this way of sucking the coffee from the spoon. You don't drink it. You slurp the coffee. With a spoon. It's cupping. Every detail counts. Each step in the coffee analysis protocol must be methodically carried out. You compromise coffee evaluation if each cup is not prepared in the same way. This is serious business.

One hour. It takes an hour to assess a table of ten coffees. And an hour goes by fast. As the time passes, each cup recites its monologue and our mission is to learn and understand their language, to decipher them. On each cup there's a number, and that number transports us to a landscape, to faces, hands, people, climates, trees, birds, visions, ambitions, learning, disappointments, love. It's all coffee. I wasn't roaming the country in my boots and hat as I'd imagined, but I was served like a queen. The terroirs and their coffees were expressed on the same table. I had only my nose and my spoon, but I tried to do the best I could to honor the work behind it. Feeling that I was the next link, that I was extending the producer's work by working on a return, a complete, exhaustive appreciation of his product filled me with joy. And above all, I brought my European cultural background to evaluate this coffee with a view to exporting it to consuming countries.