Taste transports us. Memories have taste. Caramelized plantain, coconut water, fresh cow's milk cheese. Cooking often transports me to Venezuela. Being there, and after so many years away from all those dishes I love, I've given myself a real treat. Another thing I love about this country's culture is its religious celebrations. The festivity linked to the sacred is something I haven't seen elsewhere, as much as in Venezuela. I really wanted to attend the San Antonio celebrations. The saint is celebrated to thank him for the promises he has kept, and to ask him for more, by dancing the Tamunangue. It's danced by two people and it's very beautiful to see, the partners are dancing for San Antonio so each step is danced with respect, seriousness and elegance. Juan and I didn't make it.

chapter 14

Discovering a culture through taste.

Nothing to worry about. It was a wise choice. Staying in Caracas was necessary. When we found out that I'd once again been selected to sit on the jury to select the best coffees from the best, the choice was quickly made. We'd given up leaving for Tamunangue and also to go and see the farms for the time it would take to evaluate the coffees. I couldn't be happier. I'd had the chance to taste the 180 coffees that took part in the competition organized by EICEV, where we selected 48 for the international phase, specifically those that scored over 85. These coffees would represent Venezuela in the eyes of international tasters. Now I was going to be able to share this sensory experience alongside two other Venezuelan tasters, with Q graders from all over the world. Good food and good wine leave a lasting impression when shared. The same goes for good coffee.

Italians, Spaniards, Mexicans, Colombians, Brazilians, Russians, French, Greeks... they all came to taste Venezuelan coffee. By what miracle did they end up in the same place at the same moment? Venezuelan coffee arouses the curiosity of other countries. Daniel Noguera has been a manager at Urbana Café in Cincinnati for several years. He is Venezuelan and wanted to reconnect with his country by opening himself up to discovering the coffee produced there. The EICEV is a time of many opportunities for producers and potential buyers of coffee. For me, the opportunities were numerous. As I said before, the opportunity to taste and travel around the coffee-producing regions. To meet all the key players in the industry who work for specialty coffee in their countries. To learn. To learn to taste, to smell, to think and, quite simply, to learn about coffee. The protocol is established, defined, but one thing I've been able to learn from experience, from days spent cupping, by doing, is to create my own approach. It's deciding how I'm going to approach the cups of coffee based on how comfortable I feel. In fact, time passes so quickly that you have to decide how much time you want to dedicate to each step. In this way, I take ownership of the actions that allow me to get to the end of the tasting. Smell the coffee once, twice, three times, pour in the water, break the crust then wait 12 minutes since the water has come into contact with the coffee, before it's too hot for me, although some people consider it necessary to taste hot coffee. Everything is valid, everyone finds the best way, their way of doing justice to coffees. Some coffees surprise you right from the smell, making you want to discover more, and each step of the protocol reveals more of its personality. Some coffees surprise as they go along. Sometimes it takes 20 minutes for the coffee to reveal the full potential of its attributes. Every day was full of surprises and new curiosities. Venezuelan coffee is very varied. There are profiles to suit all tastes, and in the deliberations after each tasting table, opinions converged on a quality coffee. The nuances of taste diverged, a clear sign of the complexity of the cups. I love being able to develop my senses and broaden my references with Venezuelan coffee. I felt that my approach to evaluating coffees was really based on what I perceived in the cup. I've sometimes thought of Kenyan, Colombian or Ethiopian coffee when tasting certain coffees.

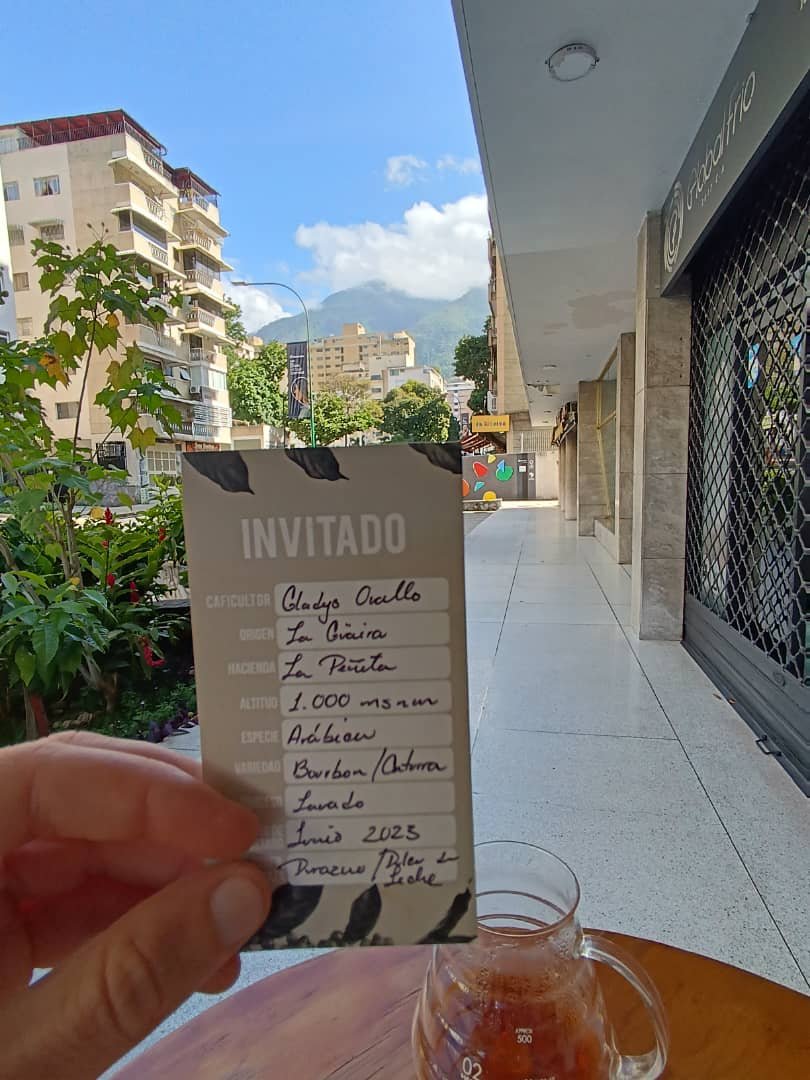

It's a heavy responsibility, and it's a thought that never left me. While deep down I wanted all the producers to be rewarded for their coffee, I knew that making the choice was important, was going to be decisive for the future of specialty coffee in Venezuela. We only had taste to judge the coffee and nothing else. As far as I'm concerned, there are many other parameters for judging and qualifying a coffee. The production system must be in phase with environmental issues. But in my case, all I had was taste and my powers of observation. First of all, washed coffee is the most widespread process in Venezuela. Lavado fino. Washed coffee is coffee that has undergone wet processing after the cherries have been harvested. The cherries are passed through a washing station, which pulps the coffee cherries and ferments the beans to produce a bean with varying degrees of mucilage. The aim of this process is to leave as little mucilage as possible to allow the coffee, its variety and terroir to express themselves as honestly as possible. At least, that's how I see it. This is the treatment commonly used in commodity coffee. Buyers generally only buy washed and dried coffee. Based on their ancient knowledge and methods, coffee growers who focus on specialty coffee produce mostly washed coffee. So this is largely what made up our tasting tables, leaving little room for natural, honey and modulated coffees. And just as well, I love washed coffee. And I was able to appreciate all the subtleties in all these coffees. Some are sweet, cocoa-like, honeyed, while others lean more towards acidic, fruity tastes. I love the sincerity with which a good washed coffee expresses itself. Without artifice, it reveals the complexity of its personality without overdoing it. It's a coffee that manages to make a statement without pretension. For me, it's the processing that makes the climate, the land, the ecosystem and the producers speak for themselves. The Venezuelan terroir speaks for itself through these many cups of coffee.

René Orellana is a man with his ear to the ground. He initiated the quiero1café coffee shop project, an important venue for specialty coffee in Caracas. He is a man who has sought to enhance the value of Venezuelan products and production. He loves good products and human endeavor. In his coffee shop, expert baristas offer coffees from every region of Venezuela. Trujillo, Mérida, Miranda... there's something for everyone. Especially if you want to discover the country and be impressed by what is produced locally. René's challenge is already to surprise Venezuelans. Getting them to know and accept local know-how is a challenge. In Venezuela, it's easy to turn to products from elsewhere. By reintroducing himself to Venezuelan coffee, he has rekindled his goodwill towards his country and, above all, his pride in belonging to this culture. He was a person with whom I'm happy to have shared this moment full of discoveries for me and full of reunion for him. There's a definite richness in Venezuela's specialty coffee. All that remains is to recognize and reveal it.